by Cathlyn Mae Botor

The striking tek sound of a light wooden stick (pat-ik), fixed with sharp pomelo thorn, hand-tapped repeatedly onto my ankle surprisingly seemed like music to my ears. A painful rite of passage renowned as Batok tattooing signifies bravery beyond beauty. Tattooed Butbut women in Buscalan, Grace Palicas and Elyang Wigan, spearheaded by legendary centenarian Apo Whang-Od, have perfected the art of pagbabatok as a social practice for a successful headhunt and a symbol of fertility.

The striking tek sound of a light wooden stick (pat-ik), fixed with sharp pomelo thorn, hand-tapped repeatedly onto my ankle surprisingly seemed like music to my ears. A painful rite of passage renowned as Batok tattooing signifies bravery beyond beauty. Tattooed Butbut women in Buscalan, Grace Palicas and Elyang Wigan, spearheaded by legendary centenarian Apo Whang-Od, have perfected the art of pagbabatok as a social practice for a successful headhunt and a symbol of fertility.

In Kalinga, cultural pilgrims endure treacherous hours of travel to trek the hilly part of the Cordilleras up the Luzon highlands to take part in the ritual. Batok tattooing is a badge of honor that I had them embellish on my skin to carry with me to the grave, hoping it lives on for the next thousand years or so.

I often hear stories about Apo Whang Od’s legendary tattoo art, but it never occurred to me that one day, I’d get inked by one of her protégés.

My legs felt numb and worn out after sitting for almost 15 hours inside a 12-seater van. It was an incredibly long and winding journey to Kalinga. We were told to pack light, so per usual, I only brought my backpack, camera, and a neck pillow to cradle my head throughout the journey up north.

cradle my head throughout the journey up north.

My phone signal started dropping out when we began traversing the Bessang Pass Road. We drove through the twisty mountain roads and passed by some collapsed pavements due to recent landslides along Sagada and Bontoc, Mountain Province on the way to Tinglayan, Kalinga.

The seemingly endless twisted roads did not allow any of us to eat or sleep properly. I immediately dozed off, but my head repeatedly hit the window on the edge of my seat every time the van made sharp turns, thus resulting in a huge bump on my forehead.

At exactly midnight, we reached a tourist checkpoint, just 30 minutes away from our destination. Sleepy and tired from the seemingly unending journey we’re on, each of us reluctantly disembarked the van to register and sign our names on a piece of paper.

At exactly midnight, we reached a tourist checkpoint, just 30 minutes away from our destination. Sleepy and tired from the seemingly unending journey we’re on, each of us reluctantly disembarked the van to register and sign our names on a piece of paper.

After hours of resisting the urge to pee, I found myself looking for a loo in the middle of nowhere. Except for the police station, the surroundings appear almost pitch black with only the swooshing of a river nearby. Thanks to the sky full of stars, it wasn’t totally dim.

We reached the jump-off point to Buscalan Village at around 45 minutes past midnight. A pack of dogs was madly barking at us, so instead of leaving the van, we were stuck inside for hours on end to catch some sleep before our scheduled trek at the crack of dawn.

I was awakened by a sour rumbling in my stomach. We were about to begin hiking up the hilly terrain. We were still half an hour’s hike to our destination, yet my travel companions showed no signs of fatigue, as if we were all ready and fully awake to conquer the steep trail.

awake to conquer the steep trail.

The early morning sunlight gently kissed my cheek while striding through the crisp mountain air. We made our way past the only downhill track towards a charming pedestrian suspension bridge. From here on out, the rest of the trail will be uphill. The timed stops along the way allowed us to hydrate and catch our breaths.

We passed by the first house at the village entrance. In my mind, I envisioned the homes to be traditionally built, like huts. It turned out that the houses resembled those from where we came from, which are also made of concrete cement and corrugated roofs. One of the villagers caught my eye—he was building a riprap wall out of what looked like huge limestone rocks to protect the soil from erosion induced by torrential rains in the mountains.

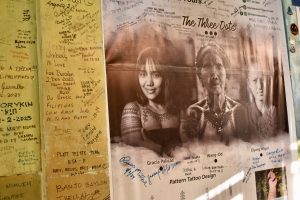

Just a stone’s throw away from Buscalan Elementary School, we finally reached the tattoo site of the legendary Apo Whang-Od and her mentees, Grace Palicas and Elyang Wigan. Despite not meeting the fabled mambabatok, we were lucky enough to meet the two ButBut women who have been practicing the traditional hand-tapping tattoo for the same reason Whang-Od does.

Just a stone’s throw away from Buscalan Elementary School, we finally reached the tattoo site of the legendary Apo Whang-Od and her mentees, Grace Palicas and Elyang Wigan. Despite not meeting the fabled mambabatok, we were lucky enough to meet the two ButBut women who have been practicing the traditional hand-tapping tattoo for the same reason Whang-Od does.

Inside were walls laid out with varied mementos consisting of pictures, IDs, and even personal documents like diplomas and old ATM cards of past travelers who visited Buscalan. While waiting for my turn to get inked, our guide offered a warm cup of freshly brewed Kalinga coffee.

Eventually, it was my turn. I remember batok artist Grace as she struggles to draw an arrowhead pattern on my ankle. I laughed, as did come a sudden realization that I was born with a flat foot. She then proceeded along, with no hesitation, to gently but firmly hand-tap the light wooden stick attached with a sharp thorn onto the soft skin of my right foot. I’m well aware of my high pain tolerance but the throbbing ache it caused suddenly made me question my impulsiveness.

Living in the mountains for two days taught me how to slow down. Life without Internet is impossible to fathom. It sounds like a nightmare, not being able to check my phone all the time. But being surrounded by nature with a view this spectacular, I wouldn’t trade this moment for a quick Facebook scroll.

As I was gazing up at the starry sky, I wondered where my feet would take me next. No matter how far I wander, I’ll take the places I’ve been to with me, forever etched in my heart.

Before I left, I glued my Polaroid picture up the ceiling of a thatched roof, beside pictures of previous Buscalan goers who got inked by the famed mambabatoks. My now-wounded ankle has become a precious hand-tapped memento to remember Buscalan by.

The sharp shooting pain I feel every time I try to step with my foot reminds me that I’m alive, and that alone makes the pain bearable. That pain lingers, along with the extreme sorrow and regret all of us inevitably experience at some point in our lives. But fear not, as these painful experiences will keep us grounded, back on our feet.